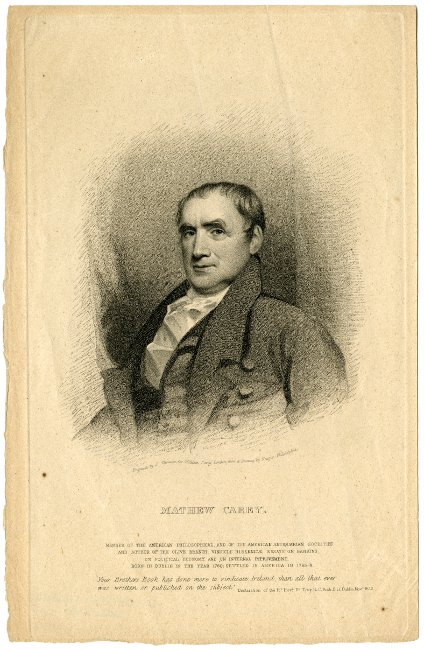

Mathew Carey: Publisher and Politician

Philadelphia has a long and storied history in the printing and publishing worlds. Here was founded one of the nation's earliest papers mills as well as its first prominent newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette. Ranking high among America's early publishers was Mathew Carey (1760-1839).

Mathew Carey was born in Dublin, Ireland; and he immigrated to America in 1784 with nine years of experience as a printer and publisher already under his belt. When the Marquis de Lafayette, who had met Carey a few years earlier in Paris, learned of his arrival in America, he sent Carey a check for $400 with which to establish his own business. Naturally, Carey chose publishing and bookselling. He formed Mathew Carey & Company in 1785, which went on to become one of the city's and the nation's most successful publishers. His original company changed names and hands over the decades and in the early 1900s became known as Lea & Febiger, a well-known publisher of medical works throughout much of the twentieth century.

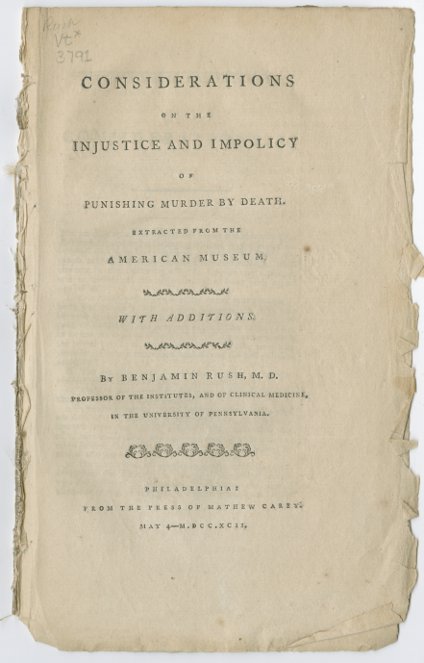

During the course of his own career, Carey published over forty medical works; however, he also published broadsides, novels, atlases, bibles, and political titles, including some of his own writings such as Vindiciae Hibernicae (1819), New Olive Branch (1820), and Essays of Political Economy (1822). Carey devoted his life to political economics after he left the publishing business in the early 1820s.

Recently, HSP was introduced to a new blog that speaks to Carey's involvement in politics: Secession And Mathew Carey. By way of introduction, here is the text from the blog's "About Us" section:

Mathew Carey (1760-1839) used the pseudonym of “Caius,” a character from King Lear who was loyal but blunt. When Mathew Carey feared New England would secede from the Union, he read everything he could find on the history of civil wars. In that spirit, “Caius” offers a historical perspective for political discussion.

For years, Mathew Carey languished in obscurity. Now, partisan politics are increasingly rancorous. Threats of secession are making headlines. Mathew Carey’s works have new relevance.

This blog offers intriguing glimpses into Carey's political life as well as the history of New England after the Revolutionary War. It's an interesting and pertinent source for Mathew Carey researchers, for folks who are interested in the history of this nation's growing pains during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, or for those who want to delve into the workings of United States–British relations of the 1800s.

For further information on Mathew Carey and his works, HSP has several relevant collections, including the Edwards Carey Gardiner collection (#227A) and the Lea & Febiger records (#227B). Plenty of additional resources, both published and unpublished, can be found in our online catalog Discover.

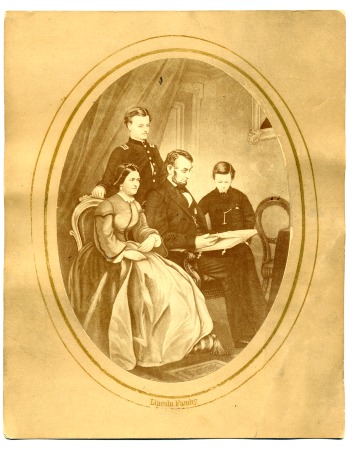

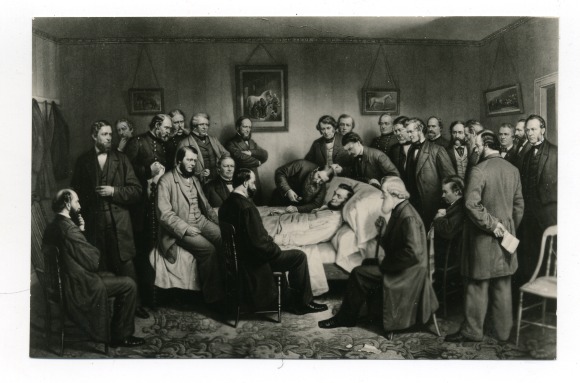

The artist William Bell Waugh, for example, has placed a bust of Washington right over Lincoln's shoulder. Nonetheless students can look at the background of the image for clues to the accuracy of the movie setting. Are the clothes similar? The furnishings? Students can learn how to use these visual clues to date artifacts and historical events. They may discuss how important is it to a film to get these details correct. Does it change the story if the historical context is altered?

The artist William Bell Waugh, for example, has placed a bust of Washington right over Lincoln's shoulder. Nonetheless students can look at the background of the image for clues to the accuracy of the movie setting. Are the clothes similar? The furnishings? Students can learn how to use these visual clues to date artifacts and historical events. They may discuss how important is it to a film to get these details correct. Does it change the story if the historical context is altered? What elements do the two images share? How are they different? Do you feel the same emotion from each? Which one matches the feel of the movie better?

What elements do the two images share? How are they different? Do you feel the same emotion from each? Which one matches the feel of the movie better? the movie scene. Now compare it to

the movie scene. Now compare it to