A Pinch of History: Amelia Simmons's Apple Pie

One of the most interesting articles I have come across randomly browsing the Internet discussed last meals of famous inmates on death row. There are several outrageous feasts, but the most popular food of choice is apple pie a la mode. Why, you might ask?

To many, apply pie is quintessentially American. Yet its unmistakable scent holds specific memories. Memories of Thanksgiving and Christmas evenings spent gathered around the table with my large family. My mouth is watering as I write this post, as I am thinking about the remainder of this pie in my refrigerator and how I cannot wait to heat it up in the microwave when I go home. Other favorite desserts of the thirteen colonies were different variations of puddings, mini cheesecakes, bread puddings, and candied fruits.

Apple pie dates back to the 14th century, printed in a recipe book by Geoffrey Chaucer. It was referred to as "English pudding". This first variation consisted of a pastry crust, apples, figs, pears, & raisins. Interestingly, the British recipe did not call for sugar. It is believed the pears were to provide the sweetness; sugarcane, at the time, had to be imported from Egypt and was very expensive. Apple pie began to appear in America in the 17th century.

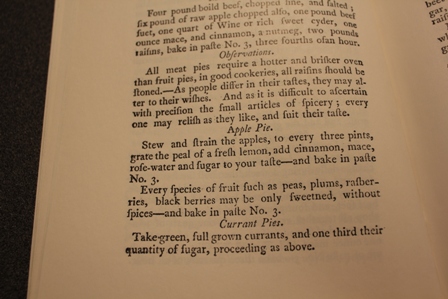

Like the cookbook of Hannah Glasse profiled in my previous post, Amelia Simmons's cookbook was published during her lifetime. However, HSP’s copy is a modern facsimile, so I was not as afraid to touch it as I was with Glasse’s book.

Simmons channeled Hannah Glasse when she garnished her cookbook with a lengthy title:

American Cookery, or the art of dressing viands, fish, poultry, and vegetables, and the best modes of making pastes, puffs, pies, tarts, puddings, custards, and preserves, and all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plum to plain cake: Adapted to this country, and all grades of life.

This book is significant because it is the first cookbook published in the 13 states upon its publication in 1796. Before that, the cookbooks in use were British or were shared through families, such as that of Martha Washington, also featured in a previous post of mine. The recipes combine British methods and tradition with American products, as different ingredients were available on these different continents. The book is also important as it calls for a chemical leavening of bread, a novel idea. This ingredient is an ancestor of modern baking powder. Bread was normally leavened with yeast at the time.

Very little is known about Amelia Simmons, other than that she was an orphan who may have lacked formal education. She paid the publishing and printing costs of her cookbook herself, as the title page says "For the Author". It was not bound in hard covers. This cookbook was very simple to read and understand, which I think just makes it easier to prepare meals the way they were meant to be.

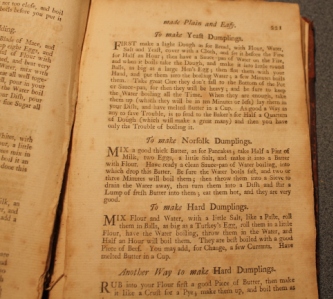

After my last foray into the world of lettuce tarts, I chose apple pie because it sounded edible; I might be able to find all of the ingredients, and who doesn’t love apple pie? Maybe my family would actually eat this recipe (unlike Martha Washington’s lettuce tart—not a popular one). The original recipe reads:

Apple Pie.

Stew and strain the apples, to every three pints, grate the peal of a fresh lemon, add cinnamon, mace, rose-water and sugar to your taste—and bake in paste No. 3.

Every species of fruit such as peas, plums, rasberries, black berries may be only sweetened, without spices—and bake in paste No. 3.

Don’t judge me—after the lettuce tart I decided to use store-bought pie crust, not paste No. 3. If you ever want to bake a pie, use Pillsbury. It was so buttery and flakey. Unfortunately, I could not get my hands on mace. I planned to bake this pie after my internship, so I had my mom run to the store while I was here. I told her to look for mace in the spice section. When I came home, she told me how she was looking for pepper spray. I love how she is concerned for me living and going to school in North Philly, as that is why she assumed I meant pepper spray. I improvised with some nutmeg, as mace is the shell of a nutmeg. Rose water is not so easy to come by, either. It was used to add flavor to recipes, so I tried a drizzle of melted butter.

This pie is delicious in its simplicity. It had the taste of conventional apple pie, but not so much artificial sweetness. It’s like a clean-eating apple pie (if pie can be clean-eating). My mom said it didn’t feel like she was eating a load of junk.

Besides preparing the crust, I also dreaded peeling the apples. Simmons doesn’t specifically say to, but I always do when preparing my cinnamon apple topping for crepes. For this task, I enlisted the help of my boyfriend. Colonial women most likely had their daughters helping them in the kitchen, so I felt justified in requesting a little help too! He decided not to conform to traditional vanilla and ate his apple pie with coffee ice cream on top. It’s all we had in the freezer, but you can use whatever flavor ice cream you please.

I actually enjoyed baking this pie, and I normally much prefer cooking to baking. Maybe it's because I cheated with pre-made pie crust, but either way I liked the feeling of preparing a simple apple pie the way it would have been done in the 18th century when the food was extremely popular. Simple and without all of the added artificial ingredients.

I think apple pie has withstood the tests of time in the United States because Americans love desserts and they love apples; it is easy to prepare and requires few ingredients; and it has become a symbol of patriotism and tradition. As the world increasingly becomes nutritionally conscious, the fate of apple pie as we know it could be in danger. However, as someone who likes to eat as healthily as possible, I have found many variations that provide the same satisfaction. Go crustless and create an apple "crisp" with a granola or quinoa topping. There are also countless recipes for grain-free/gluten-free crusts using almond meal or coconut flour. Then make the filling similar to mine, nothing but apples and spices, and perhaps substitute the sugar for all-natural Stevie or honey! Top it with low fat Cool Whip instead of ice cream and it's complete. Keeping the legacy alive.

Amelia Simmons’s Apple Pie

2 Pillsbury refrigerated pie crusts, brought to room temperature

3 Granny Smith apples

3 tbs. butter, divided

Granulated sugar

Cinnamon

Nutmeg

Lemon juice

Cooking spray

1. Preheat the oven to 375 degrees and spray a pie dish with cooking spray

2. Unroll your first pie crust and line the pie dish

3. Peel, core, and chop the apples

4. Sprinkle sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg on the bottom of the pie crust

5. Add apples and spread them to fill the dish

6. Cover with more sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg

7. Melt 1 ½ tbsp. butter and drizzle it over the apples

8. Add a drizzle of lemon juice (I didn’t use much)

9. Unroll your second pie crust & cover the apples

10. Seal the sides of the crusts together with a fork and poke holes in the center (I am not sure why I do this; I think I vaguely recall being taught to in high school cooking class, so the pie doesn’t blow up or something)

11. Melt the remaining butter and brush the top crust so it becomes golden brown when baking

12. Bake for approximately 30 minutes or until the pie is browning

13. Allow to cool fully

14. Serve warmed, topped with whatever toppings you would like!