Hannah Glasse’s cookbook is the oldest of the four that I chose to focus on, with the exception of Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery (which holds recipes dating to Elizabethan times). Glasse was English, but her cookbook was widely used on the American continent.

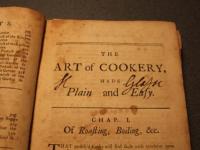

Published in 1755, Glasse's cookbook looks its age. The front cover is completely detached and pages fall out left and right. When researchers hold the book in their hands, tiny pieces of paper sprinke the table below.

I was terrified of damaging a valuable piece of history. For these reasons, I was more comfortable reading an e-book version on the computer. It was an exact facsimile scanned onto the Internet. The photos are of the original book, which it now safely back in its protective acid-free box.

As I stated in my second post, Hannah Glasse’s cookbook is a published work created for instructive purposes. It felt less personal than Martha Washington’s or Mary Plumstead’s handwritten books. The book bears a title reflective of its time: The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy; Which far exceeds any Thing of the Kind ever yet published. She asserts in the introduction that the purpose of the book is to simplify the art of cooking for the servile classes so that servants may better provide for their masters. To this, I would say that Glasse has succeeded. Her book provided the most instructions on how to choose the best ingredients, the most basic instructions on tasks like roasting or boiling, the most recipes in total, and the most explicit recipes— I was left with little questions on how to execute the recipes because she provided enough steps and insight in the first place. The handwritten books are much vaguer; they were probably thoughts scribbled down in live action in the kitchen. Amelia Simmons’s cookbook is published as well, though much shorter and less in-depth.

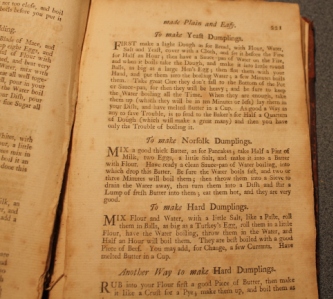

The other challenge I encountered with Glasse, aside from the fragile condition of the book, was her use of the formal “S”. I come across these stylized characters in my history classes while exploring primary sources. Eventually you get used to it, but when I first begin I cannot help but read with a slight lisp as the “S” looks like an “F”.

Compared to others included in Glasse's work, this recipe was extremely simple. I also thought the recipe was adorable, how Glasse added her own opinion at the end even though the book was a more formal work. The original recipe reads:

“To make Norfolk Dumplings, Mix a good thick Batter, as for Pancakes, take Half a Pint of Milk, two Eggs, a little Salt, and make it into a batter with Flour. Have ready a clean Sauce-pan of Water boiling, into which drop this Batter. Be sure the Water boils fast, and two or three Minutes will boil them; then throw them into a Sieve to drain the water away, then turn them into a Dish, and stir a Lump of fresh Butter into them, eat them hot, and they are very good.”

To say the least, this recipe fits in to how many might imagine colonial cooking to be. It was slightly tasteless and bland, according to our modern tastes. The addition of the butter at the end is definitely necessary, and I am not even a huge fan of butter.

I have no measurement of the flour, but you need A LOT to create sticky dough that can hold its own. Cooking often cannot come down to exact measurements. My dumplings looked like shapeless blobs because, rather than roll them into neat little balls, I felt that I should just drop handfuls of dough into the boiling water. I had never prepared a dumpling before, so I had no idea what shape they should be. I am still developing as a cook, and I have much to learn from these 18th-century women.

Hannah Glasse’s Norfolk Dumplings:

1 cup milk (I used 1% reduced fat)

2 eggs

Whole-wheat flour

Sea salt

Butter

1. Bring a saucepan of water to a rolling boil

2. Meanwhile, beat the eggs in a large mixing bowl

3. Add milk and stir to combine

4. Sprinkle some sea salt in before adding the flour

5. Begin adding flour little by little, stirring between. You want the liquid ingredients and dry ingredients to form a dough (I tried to get it to pizza crust or pie crust consistency)

6. Once the dough is cohesive, drop balls into the boiling water

7. After about 3 minutes, or when the dumplings are solid and cooked, drain them in a strainer

8. Place the dumplings in a bowl and stir a decent glob of butter into them while they are still hot, so that it melts fully—and enjoy!

Perhaps the addition of some honey & cinnamon would help to liven these dumplings up. Or they could simply serve as a dinner roll-type food!

Regardless of how each recipe is turning out, the experience of cooking from a historical cookbook is indescribable. I find myself laughing, grimacing, questioning, and feeling very excited to taste the results. Every recipe is literally an adventure-- who would have thought cooking could be so complicated and intriguing!