As a foodie, one of my favorite things to do is explore the city discovering new restaurants and cafés to try. My personal focus is on the use of new and fresh ingredients and the nutritional quality of the items offered. Philadelphia is a gold-mine for my hobby; there are hidden restaurants you would never even hear of without having explored the city on your own. Each establishment I venture into has its own ambiance, which can often help you make a decision on where you want to eat. Sometimes I want to eat outside on the sidewalk, sometimes I want a quiet café style, and sometimes I want a big and loud restaurant.

I also enjoy people-watching and meeting the more frequent customers at each place I find; they help me see a wide variety of perspectives, not only on food culture, but anything else that may come up in conversation. I have had some of my best memories in randomly-discovered Philadelphia restaurants.

After trying to make a mental list of all of the eclectic places I’ve found in this city, I began wondering about the foodies of the 18th century. Where did they go when they wanted to socialize while around food and beverage?

After taking a Colonial America class at Temple, I immediately recalled an entire lecture devoted to taverns. There are several scholarly works based solely upon tavern-going practices of the early United States, such as Peter Thompson’s Rum, Punch, & Revolution: Taverngoing & Public Life in Eighteenth Century Philadelphia, published in 1999.

Philadelphia was founded as an anomaly. It was based upon notions of tolerance and order. Christ Church on 2nd and Market Streets, the first Protestant church, stood alongside Quaker meetinghouses. On the streets closest to the river lived wealthy merchants alongside poorer artisan neighbors. Diversity ran rampant, much like it does in Philadelphia today, and that diversity was a prominent characteristic of 18th century taverns and food life. Men of all classes and ethnicities drank alongside each other, with the exception of apprentices, slaves, Native Americans, and most women—but this does not mean the men were always tolerant of each other. Brawling was a frequently-used means of settling tension.

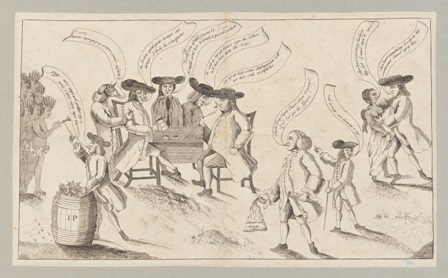

As demonstrated by Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia was characterized by social mobility. Franklin came to the city in 1723 as a runaway printing apprentice and established himself quickly as a gentleman, founding significant institutions such as the American Philosophical Society and the Library Company of Philadelphia. A 1764 political cartoon depicts Franklin conversing with Quakers in a tavern setting during that year's election of the Members of Assembly:

(Click on the image to view The Quakers and Franklin on HSP's Digital Library.)

In this city, civil discourse was viewed as a bridge across class rank and ethnicity. Although appearance and wealth were important, men of all classes were able to express their opinions regarding public matters within tavern walls. Men from disenfranchised groups could voice their thoughts and possibly influence someone who could vote. Drinking was a means of establishing a connection between men who may have lead very different lives outside the tavern.

City Tavern is the most well-known colonial tavern, although it is not original; the initial building burned in 1853 and was subsequently rebuilt and remodeled. Man Full of Troubles on 2nd and Spruce Streets is considered the last colonial tavern in existence. It is permanently closed but still intriguing to pass by. Restaurants today have short, modern names, often only one word. I now wonder why this is; I greatly admire the creativity of tavern names in colonial Philadelphia. Maybe if you did not feel like going to Man Full of Troubles again, you could head over a few blocks to George Bows Out With a Blowout.

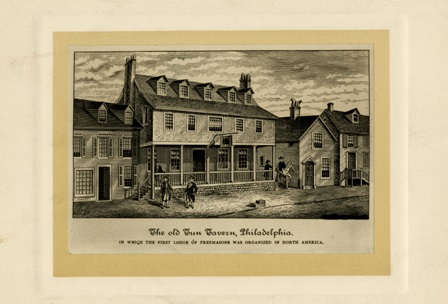

Today, we go to restaurants and bars to enjoy delicious food and drink and to interact with our peers. Taverns of the 18th century had an even larger importance. They often served as a location for clubs to meet, merchants to conduct their trade, travelling businessmen to find new customers, and politicians to campaign across class lines. Tun Tavern, formerly located on Front Street, is known as the birthplace of the United States Marine Corps in 1775.

(Click on the image to view The Old Tun Tavern, Philadelphia, in which the first lodge of the Freemasons was organized in North Americ on HSP's Digital Library.)

In a time where socialization had to be done face-to-face and not through technological devices, taverns were vital to the functioning of society. Taverns were a place of gathering where men of all social classes could express their ideas and opinions together. The Revolution was fueled by a rapid spread of ideas, a large amount of which took place in colonial taverns. Food and drinking practices were as vital to cultures in the colonial era as they are today.