In the field of conservation there are degradations and vulnerabilities that are brought about by circumstance and environment, and then there are those that are endemic to an object, and fall under the poetic epithet of “inherent vice.” Perhaps one of the most infamous and widespread potentialities of inherent vice in the realm of historical manuscripts is that of iron gall ink. So named for its composition of gallotannic acid and iron salts, iron gall ink was the writing ink of the Western world from the late-Middle Ages up through the 19th Century. The prevalence and popularity of this ink for so many centuries was due in greatest part to its outstanding permanence – a quality which with time has sporadically been known to shift from virtue to vice.

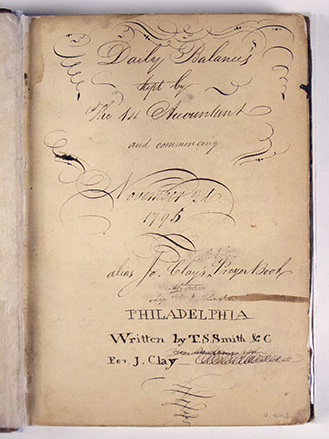

A title page written in iron gall ink from the Bank of North America collection: vol. 404.

Nearly all of the record books and ledgers in the Bank of North America collection (col. 1534) are written in iron gall ink, as are many of the other 20 million manuscripts held here at the Historical Society. In the Western world, the ubiquity of iron gall ink lasted well into the 19th Century when the proliferation of metal nibs and fountain pens required a writing liquid that didn’t result in abundant rust and a “gumming up of the works.” When considering an ink that rusts steel, it is easy to imaging the potential havoc it might wreak on the comparably delicate substrate of paper.

An example of iron gall ink corrosion from a collection of miscellaneous marriage certificates (collection Am .10155)

Oak galls from trees in the Aleppo region of Turkey.

Iron gall ink is comprised of four essential ingredients: oak galls, iron sulfate, gum arabic, and water. Oak galls are an abnormal outgrowth that can be found on oak trees, and are an especially rich source of tannins. The characteristic blue-black of iron gall ink when it is newly written is the result of a chemical reaction between tannic acid and iron sulfate. For hundreds of years before such a reaction was ever applied to a writing fluid, both oak galls and iron sulfate were used in the dying process – oak galls as a coloring agent, and iron sulfate as a mordant. As an ink, iron gall acts as a sort of dye, searing itself into the paper and bonding with the fibers; the result is indelible, being both lightfast and waterproof.

Gum arabic and iron sulfate, ready for ink making.

A fresh batch of iron gall ink, made at HSP in September of 2014.

Traveling back a few millennia, it goes without saying that the advent of writing was revolutionary. Knowledge was suddenly unencumbered by the limitations of a lifespan and the pitfalls of remembrance, and acquired an unprecedented potential to live on for centuries after its author had passed. Or at least it might live on, if the marks that conveyed the meaning could actually be made to endure.

By way of Late Latin (encaustum) and Old French (enque), our English word “ink” derives from the Greek enkaustos – a shared great-grandfather of another English word, “caustic:” to burn, to etch. It is fitting then that humankind’s quest for a permanent writing fluid should find its apparent success in an ink that literally burns itself into the surface of the page.

Detail of a page from the BNA collection; here the iron has started to migrate and the writing is now visible from the opposite side of the page.

Unfortunately the very reason that iron gall ink holds up so well initially is also at the heart of its eventual degradation. The acidity of the ink over time can begin to attack the very paper that supports it. Historically iron gall ink was made by hand, meaning that while a majority of these manuscripts may be written with ink of the iron gall ilk, the actual chemical makeup can vary greatly based on the recipe, the maker, and the availability and purity of ingredients.

Having an ink with a well-balanced chemistry is crucial. Because of the iron sulfate, all iron gall inks contain a tiny bit of sulfuric acid; the tannins in the oak galls can actually serve to neutralize this acidity, so long as the molecules remain bonded. Iron rusts, and so it follows that water would be the bitter foe of manuscripts containing an iron-based ink. Exposure to moisture or elevated humidity can cause these molecules to breakdown, and the corrosive iron can begin to migrate and attack the substrate.

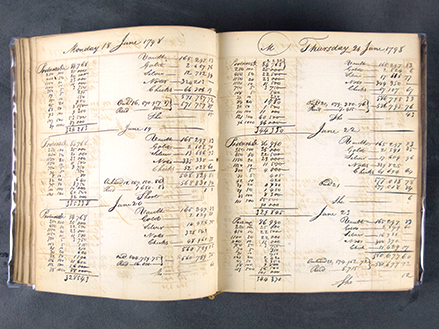

A spread from the BNA collection (vol. 447). Notice how the ghost of the writing has imprinted, or burned onto the facing page.

From the BNA collection (vol. 348): an example of iron gall ink that has etched into the suede surface it was applied to.

For museums and special collections libraries, maintaining appropriate climate levels is of the utmost importance. So long as they are not exposed to excessive moisture, most iron gall manuscripts will last for years to come, but it is still inevitable to encounter books and documents that are suffering from aggressive ink corrosion. Areas where the ink has been applied more heavily are especially vulnerable, as are papers that have not been adequately sized as this allows the ink to permeate more completely.

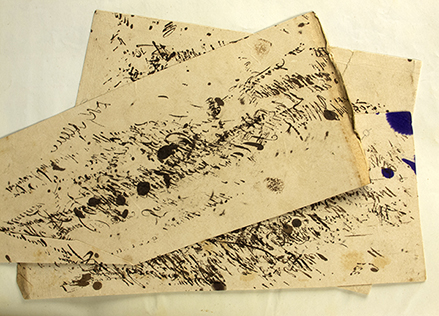

Blotter papers from the BNA collection, used to blot the ink when it is freshly applied to prevent smudging while wet.

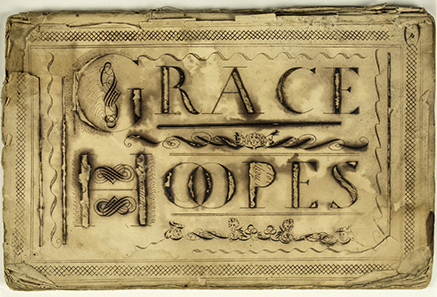

Evidence of excessive ink corrosion and losses in the company of water damage. From an 18th Century school book, belonging to Grace Hoopes (Collection 1066), 1710.

Detail of the above, here shown with white paper.

By far though, the greatest culprit is water, and excessive ink corrosion is often coupled with staining and other telltale signs of water damage. The certain peril of exposing iron gall ink to water presents quite a challenge to book and paper conservators as many standard treatments and repairs are fundamentally water-based. Reversibility is a high priority in today’s philosophy of preservation, and water-based adhesives and humidifying are important tools in the conservator’s arsenal. To aid in the solving of this conundrum, the Conservation Department at HSP recently attended a weekend workshop at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC. Be sure to stay tuned for part II of this entry, set to appear sometime in April of 2015.

For those who would like to learn more about iron gall ink, there is currently a window display on the subject located on the first floor of HSP, across from the elevator.