To continue the theme of curiosities or treasures that lie hidden in the pages of the Bank of North America Collection, I am currently performing conservation treatment on a volume that includes several examples of revenue stamps from the years of, and surrounding the American Civil War (1861–1865). The ledger, dating from January of 1855 to January of 1872, is a book of dividends from the Lexington branch of the Northern Bank of Kentucky (Collection 1543, volume 617). There are actually a number of ledgers titled after other financial institutions within the collection, and I gleaned from the finding aid that these were banks in which the B.N.A. had made considerable investments.

At first glance, I assumed these stamps were of the postal variety – an easy mistake when you are of the mind that all official stamps are postal in flavor. Still, finding the stamps made for an especially exciting discovery. I had recently been to the National Postal Museum at the Smithsonian in D.C. where I learned that the first United States postage stamps had been issued in 1847; thus any stamps in this volume would fall quite early on in the philatelic history of our nation.

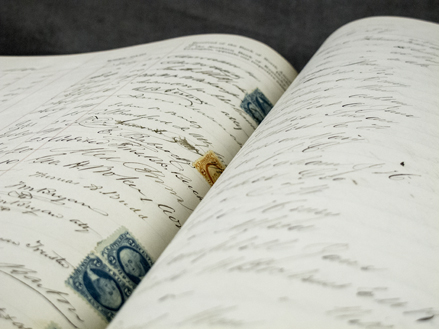

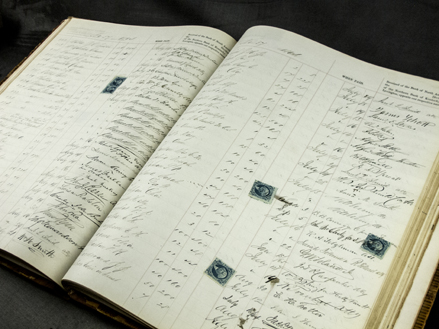

Stamps, photographed in situ, page 86.

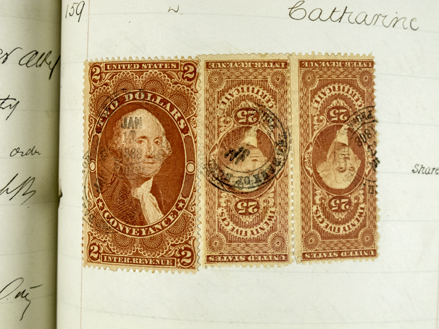

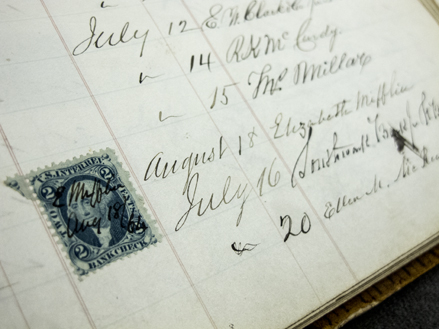

That the stamps were pasted into a bank ledger and not on an envelope or letter was, naturally, a bit mysterious, but it was still conceivable to me that postage stamps might have at some point been used as a sort of currency. This casual assumption prevailed as I set about cleaning and mending the pages, until I clapped eyes on a stamp marked with the amount of two dollars – a large denomination for a postage stamp even by today’s standards, let alone a century and a half ago. It was at this point that I began to question the postal-specific designation of the stamps before me.

Two-dollar revenue stamp (Mortgage), page 118.

Behold the fine print: United States Internal Revenue – and as History would have it, an early manifestation of the I.R.S. Postage stamps these were not. These were something else entirely.

In 1862, the United States government of the then divided nation needed a way of raising funds for the costly war with the South. The Revenue Act of 1862 sought to rectify this discretionary discrepancy with the implementation of several new taxes, and the creation of a new government office to oversee their collection. Taxes were introduced on items as diverse as playing cards, photographs, tobacco, and alcohol, and also on legal documents and financial transactions. Like postage stamps, revenue stamps could be purchased in advance and affixed to taxable items to show that the tax had in fact been paid. In the case of legal or financial documents, affixing a stamp was as much a part of completing the paperwork as signing on the dotted line.

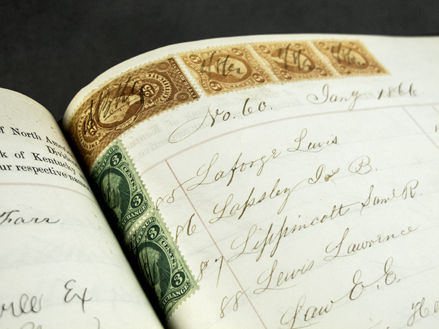

Revenue stamps: Certificate, Protest, and Express; page 88.

Revenue stamps: Certificate, Bill of Lading, Express, and U.S. Inter. Rev.; page 92.

The complexity of this system of taxation is further evidenced by the sheer variety of revenue stamps found in this single volume. On the surface they are all quite similar – each bearing the face of George Washington, and sharing the same general format familiar to even the most reluctant of philatelists. Reading the small print, however, it is clear that there were different stamps made for each specific tax, and of these, several denominations within each category. Flipping through, I found over 15 different designations, among them Foreign Exchange, Bill of Lading, Contract, Surety Bond, Inland Exchange, Mortgage, Life Insurance, Power of Attorney, and Conveyance.

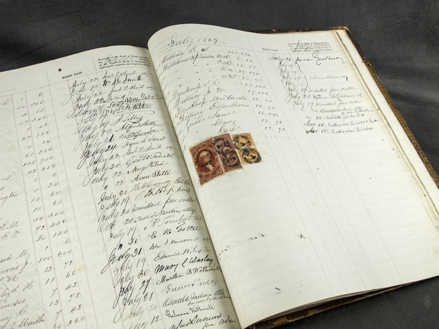

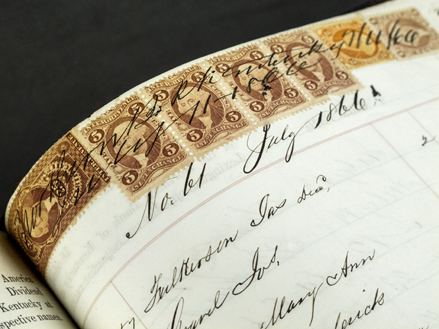

Revenue stamps: stamped cancelations; page 121.

Also like their postal counterparts, revenue stamps were usually canceled so that a single stamp could not be used on multiple items or documents. Many of these cancellations were handwritten in ink and included the date and some form of notation for the name of the person or business that paid the tax. In this ledger, most of the cancellations are handwritten, but there are also several that show no trace of having ever been canceled. Interestingly, the bank clerks also had an inked stamp made (very much like one that would be used at a post office), ostensibly for the sake of efficiency; which makes it easy to assume that there must have been a very high volume of revenue stamps that required canceling. It’s puzzling, though, that this mechanical cancellation is only to be found on a handful of the stamps, almost as if the device was frequently misplaced or not always convenient or preferred by the clerks.

Revenue stamps, hand-canceled: 'Northern Bank of Kentucky 9/11/66;' page 99.

Revenue stamps, Bank Check: both hand-canceled by patrons; page 85.

The presence of the revenue stamps in this particular volume is all the more interesting as we have not yet found any other instance of their use in the Bank of North America collection. It is also curious that the cancellation dates, from August of 1864 to September of 1870, fall short on both ends of the 1862–72 period that the Revenue Act was in effect, and also that stamps were obviously not included with each and every transaction recorded in the ledger. The explanation may be illuminated by the specifications of the 1862 law, or perhaps in the protocols particular to the B.N.A., but there is much about their inclusion in this ledger that remains a mystery. Perhaps some of our readers know more or have expertise in this area; if so, we would be delighted if you would contribute in the comments section below.