The blog was written by Maureen Iplenski, a summer intern from Temple University.

In Center City, children jump and splash in the fountains of City Hall. In West Philadelphia, residents bask in the sights of the Schuylkill River Trail. In Old City, tourists flock to catch a glimpse of the Liberty Bell. It’s summertime in the city and with the welcoming of warm weather the streets bustle with activity. However, this enlivened atmosphere wasn’t always so.

Summer in Philadelphia was once associated with a deadly calamity. Engulfed in fear, residents hid within their homes, nailing their windows and doors shut. Others hastily packed their belongings and fled to the countryside. Apart from physicians hurrying between patients and volunteers carting away the ill, the city was quite empty and unmoving. The cause of such panic was a mysterious malady that plunged its victims into a state of feverish delirium and nausea. These symptoms soon progressed to include pounding headaches and vomiting. This event, now known as the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793, was the most devastating fever outbreak in Philadelphia history, leaving nearly 5,000 dead and thousands of others fearful for their lives.

Theories of Origin

Before Philadelphia was stricken with yellow fever, the city effectively established itself as a center for intellectuals. Throughout the 1700s, Philadelphia residents organized the American Philosophical Society, the Library Company, and the College of Physicians. Despite the abundance of scholars within Philadelphia, no one could determine the cause of the fever. This led to speculation. A large portion of residents pointed to miasma as the source. The miasma theory stated that disease spread through the noxious smells of rotting organic matter. When the fever first appeared along the banks of the Delaware River, physician Benjamin Rush followed the doctrine of the miasma theory, blaming the origins of the fever on a “quantity of damaged coffee which had been thrown upon Mr. Ball’s wharf . . .” According to Rush, the coffee was so putrid that it caused great disgust and illness throughout the entire neighborhood.

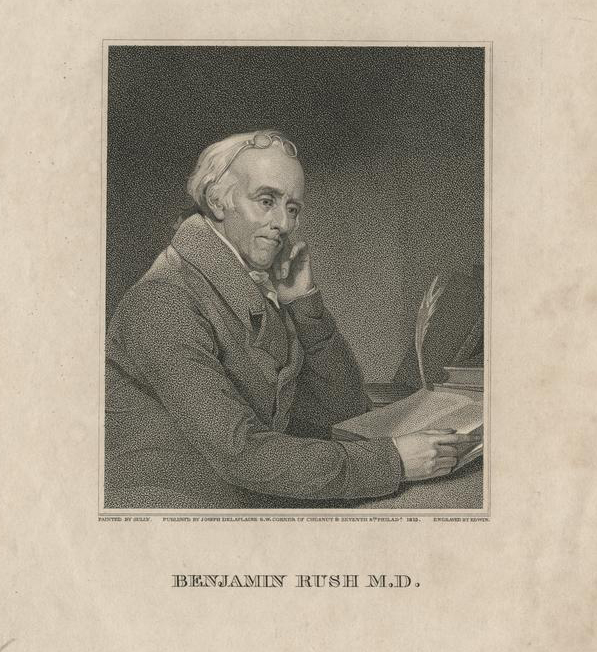

An 1813 portrait of Benjamin Rush by Thomas Sully, Historical Society of Pennsylvania portrait collection.

The theory wasn’t completely illogical. In 1793, Philadelphia had no trash disposal, water facilities, or widespread sewage lines. The city was in a state of constant filth, and putrid smells wafted down streets, into alleyways, and into homes. The devastation of Dock Creek—the city’s sole sewer system—only seemed to prove the miasma theory. Residents often used the creek to discard carrion and other forms of trash. The putrefied air surrounding the creek consequently grew intolerable. Here, the fever was most rampant, killing nearly 60% of all residents. However, many individuals in Philadelphia did not solely place blame upon the stench of the city.

At the time of the outbreak, Philadelphia welcomed thousands of immigrants into its port. Most controversial of the newcomers were the French. Approximately 3,000 French immigrants sought refuge in Philadelphia in 1793. While some were escaping the political turmoil of the French Revolution, the majority were fleeing from a slave revolt in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti). However, anti-Francophone attitudes proliferated in Philadelphia just as they did in Saint-Domingue, albeit for different reasons. Due to the Genet Affair where France tried to draw the US into its war with England and the increasing violence of the French Revolution, many Americans came to paint the French as a radical bunch. Thus, the influx of French immigrants served as a convenient explanation for the emergence of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia. To further support this idea, citizens often pointed to the fact that the fever was first found and was most rampant along the ports of the Delaware River. Although this explanation emerged from anti-Francophone sentiments, it held a shred of truth.

However, it is important to note that the majority of immigrants welcomed into the port of Philadelphia in 1793 were not French, but Irish. Naturally, they shared a portion of the blame. In August 1793, a well-to-do Quaker woman, Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker, shared news of a ship moving up the Delaware River carrying 200 to 300 Irish immigrants. Within her diary, Drinker shared that “an infectious fever [was found] on board. Orders sent them by the Govenour not to come up, ‘tis said that one or more of the passengers have ventured nevertheless.”

Theories of Exchange

Apart from the theories that aimed to explain the emergence of the fever, physicians and common citizens struggled to understand the spread of the disease. This lack of medical knowledge led to precautions and treatment that were largely ineffective.

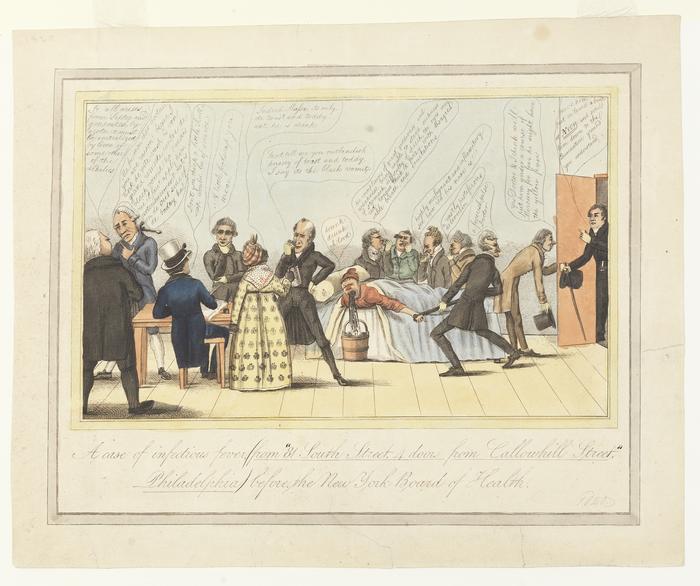

This 1820 political cartoon examines an incident when New York Physicians feared a Philadelphia man brought Yellow Fever to their city, only to learn that he was intoxicated. Historical Society of Pennsylvania medium graphics collection.

Of the most common theories of exchange was that the fever was contagious. Residents believed in this theory of contagion so wholeheartedly that many did not even dare to shake the hand of their neighbor. Those who carried the signs of mourning were quickly shunned. This misunderstanding of the fever produced devastating effects. According to Mathew Carey, a Philadelphian publisher and politician at the time of the epidemic, “the wife of a man who lived in Walnut Street was seized with the malignant fever, and given over by the doctors. The husband abandoned her, and next night lay out of the house for fear of catching the infection.” Believing his wife to be near death, he purchased a coffin. However, on entering his home, he was surprised to see his wife in good health. “He fell sick shortly after, died, and was buried in the very coffin, which he had so precipitately bought for his wife, who is still living.”

In addition to avoiding interaction with neighbors, and quite frequently, loved ones, residents employed a number of preventive measures. Some regarded the smoke of tobacco as a preventive—so many had cigars almost constantly in their mouths. With lack of knowledge about the disease persisting throughout the 1700s, others placed confidence in different methods. Carey shared that some residents were so shaken with fear of contraction that they chewed garlic nearly the entire day, even keeping cloves of it in their pockets and shoes. Those who believed in the miasma theory held a handkerchief soaked with vinegar or camphor to their noses whenever they ventured outdoors. Drinker’s diary reveals that sponges soaked in Daffy’s elixir and vinegar were used to escape the miasmatic fever.

The unknown nature of the fever instilled great fear among Philadelphia residents. Tactics bred out of desperation to avoid infection proved unsuccessful. Nearly 20,000 individuals simply moved to the countryside to escape the fever. Unfortunately, three more yellow fever epidemics would hit Philadelphia in the late 1700s, and it wouldn’t be until 1881 that epidemiologist Carlos Finlay correctly hypothesized that the Aedes aegypti mosquito was the carrier of the disease. It would take two more decades after that for scientists to accept Finlay’s hypothesis, and a vaccine for the disease was finally developed almost half a century later.

Maureen Iplenski is a student at Temple University.