In 1793, Philadelphia was struck with the worst outbreak of Yellow Fever ever recorded in North America. The fever took a devastating toll on the city as nearly 5,000 individuals died, among them close to 400 African Americans.

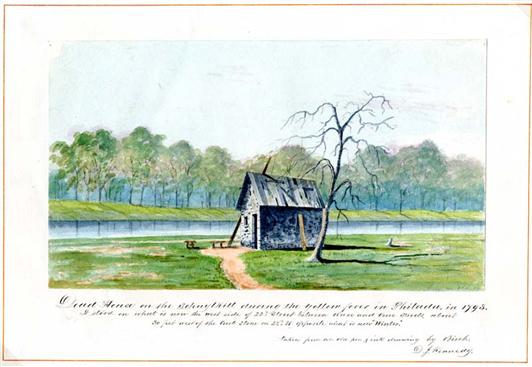

Above: Dead House on the Schuylkill during the yellow fever in Philadelphia in 1793, David Johnson Kennedy, Watercolor, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

During the frenzy and fear of the epidemic, Dr. Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration of Independence and leading medical mind of the day, wrote to Richard Allen and Absalom Jones and implored them to step in and help the sick. Rush believed that African Americans were not as susceptible to the Yellow Fever.

Allen, Jones, and many other African Americans agreed to help the sick, working as everything from nurses to gravediggers. However, Benjamin Rush’s theory was wrong, and in the end blacks died from Yellow Fever in similar percentages to whites. Allen was struck by the fever in late September and was lucky to survive when so many had perished.

By late November when the cold set in, the epidemic abated the city. Rather than being regaled as heroes, Allen, Jones, and the black community were vilified. Matthew Carey’s pamphlet A Short Account of the Malignant Fever portrayed the African American community as money-hungry opportunists and praised Stephen Girard and other whites who arranged hospitals outside of the city as the true heroes of the crisis. Jones and Allen struck back with their own pamphlet to defend African Americans.

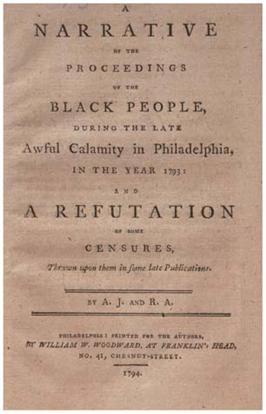

By late November when the cold set in, the epidemic abated the city. Rather than being regaled as heroes, Allen, Jones, and the black community were vilified. Matthew Carey’s pamphlet A Short Account of the Malignant Fever portrayed the African American community as money-hungry opportunists and praised Stephen Girard and other whites who arranged hospitals outside of the city as the true heroes of the crisis. Jones and Allen struck back with their own pamphlet to defend African Americans.

Right: A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793; And a Refutation of Some Censures Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications, Richard Allen & Absalom Jones (Philadelphia, 1794), The Library Company of Philadelphia.