Anyone familiar with paper will doubtless know that it tends to tear quite easily. Mending such tears is therefore among the most ubiquitous of treatments performed by book and paper conservators. In contemporary practice, the use of natural, time-tested, and reversible materials is of paramount importance. Starch and cellulose-based adhesives are prized for their strength and stability and for being water-soluble – a quality which is key to their reversibility. Partnered with the strong fibers of delicately thin Japanese and Korean papers, such mends are incredibly durable and nearly invisible – and maintain that wonderful quality of being easily removed, should a future conservator ever wish to do so.

In the Conservation Lab at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, we do a very large majority of our paper mending with wheat starch paste, which we make ourselves, cooking up a fresh batch every other day or so. The paste has only two ingredients: wheat starch and deionized water (water that has been purified of all mineral ions, such as salts and metals); and for our purposes, a ratio of 5 parts water to 1 part starch is used. The basic procedure for mending a tear or loss involves tearing a piece of Japanese paper to a size and shape only just barely larger than the area to be mended, applying paste to the back of this tissue, placing it over the tear, burnishing gently, and allowing it to dry under a small weight. Care is taken to apply mends on whichever side of the paper is less obtrusive, sometimes on both sides if additional structural support is necessary.

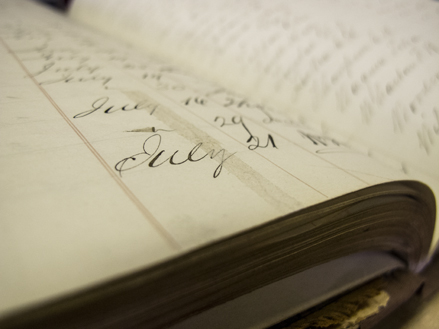

A piece of Japanese washi placed over a page from the Bank of North

America collection to show transparency.

As discussed in part one of this entry, the inherent vice and prevalence of iron gall ink in manuscripts dating from the late-Middle Ages up through the 19th Century can present many challenges for conservators. Specifically and most especially since the introduction of water can catalyze the corrosion of the ink and greatly accelerate the physical degradation of both the ink and its substrate. Since our wheat paste is over 80% water, the conundrum is clear. When faced with the task of conserving the 671 volumes of the Bank of North America Collection (#1543), with their thousands upon thousands of pages written in iron gall ink, finding a non-aqueous method for mending paper was imperative.

Those of you who have been following the conservation entries of this blog over the past year (links above and to the right) will be familiar with the name of Renate Mesmer, and the trip we took last summer to the Werner Gundersheimer Conservation Lab at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC. Among the many wonderful treatments and magical secrets gleaned from our workshop with Renate was a session on mending tears and losses in iron gall ink documents.

Wheat starch is naturally hydrophilic, meaning that it loves water and will absorb and attract it wherever possible – even from the air. So when paste is used to mend paper, the absorptive properties of the local paper fibers are compounded with those of the starch. In papers that are already impregnated with potentially corrosive ink, an increase in moisture absorption is understandably problematic.

Tools of the trade: ethanol, brush, and spatula here pictured with a page to be mended.

To avoid the dual pitfalls of starch and water, Renate introduced us to the practice of making pre-coated mending tissues with adhesives that could be reactivated with organic solvents like ethanol and acetone. The star of her tutorial was Klucel-G (Hydroxypropylcellulose), a non-ionic cellulose ether; fancy science talk for an organic, cellulose-based compound that makes for a lovely adhesive. While still being soluble in water, Klucel-G has the charm of being markedly less soluble than starch and thus less hydrophilic – excellent for our purposes.

When making pre-coated tissues for non-aqueous mends, we use the same Japanese and Korean papers as for starch-based mends – most frequently a very lightweight tengucho, a Japanese washi made with fibers from the inner bark of the kozo plant, or paper mulberry tree. Tengucho paper, specifically, is made by hand by the Hamada family in Japan; the absence of machines in the paper making process results in fibers that are very long, giving the paper a remarkable strength while still being incredibly thin. Those interested in learning more about how such papers are made can look to the link section at the end of this entry.

Tearing washi with a waterbrush and ruler.

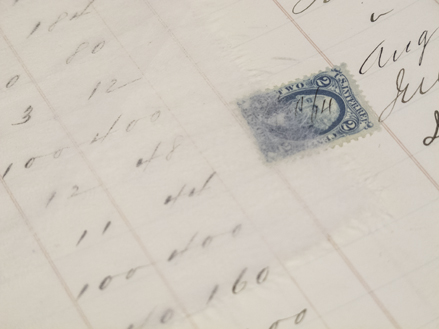

Here you can see a comparison of the fibers from a conventional, machine made Western paper next to a sample of tengucho. The papers have both been torn against a straightedge with the assistance of a waterbrush, allowing the fibers to pull gently apart as opposed to being bent or cut. This feathery edge is helpful in disguising the finished mend as well as in giving it additional points of contact for adhesion.

A comparison of Western and Eastern papers.

The first step in coating the tengucho is to mix a solution of 2% Klucel in deionized water. Alternately one could make this solution with a solvent, but since the water will evaporate well before the tissue is used, we choose to minimize our exposure to noxious fumes. Once mixed, the solution is allowed to rest overnight, to give the individual granules of Klucel time to swell and dissolve.

The tissues to be coated are then torn to size and placed in between a sheet of silicone release film (which nothing sticks to) and a small piece of window screening. The window screening allows for vigorous brushing without disrupting the fibrous surface of the paper. The Klucel is applied generously, and brushed out in all directions, thoroughly saturating the tengucho; the screening is then removed and the paper allowed to air dry.

A piece of tengucho ready to be coated with Klucel-G.

Coating the tengucho with Klucel-G.

At this point the pre-coated tissue is tested for adhesion, and if necessary a second coat of Klucel is applied. Once the tissue is ready, it can be used to mend tears and losses in areas where iron gall ink is present, and often directly over the written words – and here, the thin, gauzelike appearance of the tengucho is especially helpful. It is also important that a mend not be stronger than the original materials, as this will create tension as things expand and contract over time.

Tearing the pre-coated tissue without a waterbrush as this would wash away the Klucel.

To mend a page or document, a piece of coated tengucho is torn from the larger sheet and moistened with ethanol to reactivate the stickiness of the Klucel-G. The paper is so thin that it doesn’t usually matter which side is up, the Klucel has permeated the entirety of the sheet. It is important though, that care be taken to not over saturate the tissue with solvent, as this can flood the Klucel right out of the paper – or worse, create tide lines on the page or document, caused by the dirt and grime embedded in the paper being pushed to the limits of the moisture. Immediately after placing and lightly burnishing the mend, it should be allowed to dry under a blotter and weight. The ethanol evaporates very quickly and if this happens before the mend is set, it is possible that it will not stick and will have to be redone. To aid in this process, we created small magnetic holders which, along with a sheet of tin covered in blotter, allow us to work in short segments, moistening and immediately pressing between the magnets and tin.

Magnets holding everything in place.

Lightly dabbing the pre-coated mending tissue with ethanol.

The torn page: before.