by Karalyn McGrorty Derstine

Each issue of Pennsylvania Legacies features one Teachers’ Turn column, which provides tips for using the issue's four main articles in the classroom. This Teachers' Turn column was published in the spring 2019 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 19, no 1): Epidemics and Public Health in Pennsylvania History.

Our students live in an era of germ theory, sanitation, and vaccination. It is often difficult for them to understand an era in which the supposed greatest thinkers did not understand the vectors that caused illness or a time before vaccinations could prevent the spread of communicable diseases. This issue of Pennsylvania Legacies provides accounts of epidemics that have ravaged Pennsylvania communities and the public health responses to these outbreaks. The articles provide teachers with opportunities to bring Pennsylvania’s public health history into their classrooms in a nuanced manner. The intersection of epidemiology and social history of illness makes public health an engaging lens through which to view Pennsylvania’s past.

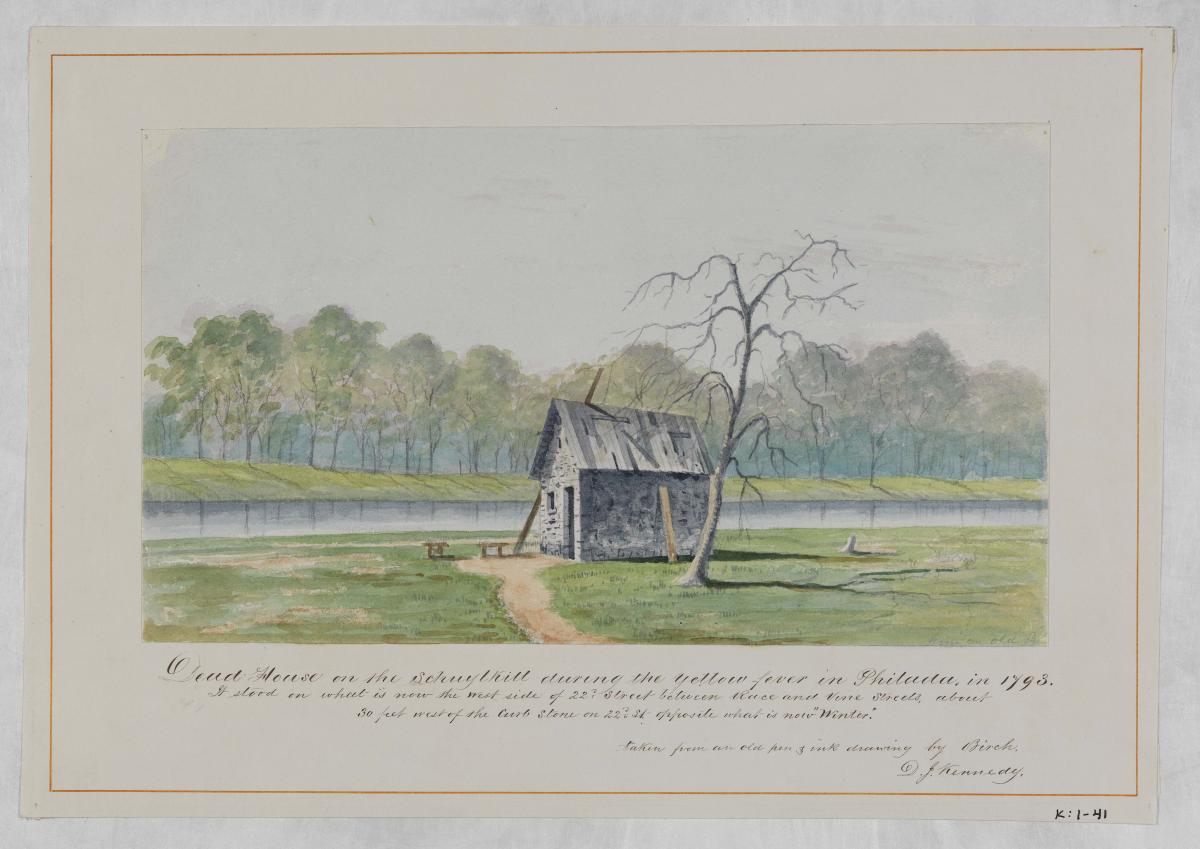

Dead House on the Schuylkill during the Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793, watercolor by David J. Kennedy. David J. Kennedy Watercolors Collection.

In the “Midst of Death”: When African Americans Saved Our Nation’s Capital

As some of the most famous figures of America’s founding era fled, a group of unsung heroes took action when Yellow Fever wreaked havoc in 1793 Philadelphia. Billy G. Smith’s article provides great insights into how the free black community of Philadelphia rallied to save the nation’s capital from a public health disaster. Despite their valiant efforts, they were met with racism in the aftermath of the deadly epidemic.

- Have students read the article. Then ask them to imagine they are Absalom Jones or Richard Allen. Ask them to write a letter sharing the efforts, work, and service of the black citizens of Philadelphia during the Yellow Fever epidemic.

- Ask students to explore a map of Philadelphia from the 1790s. Then ask them to mark the map to for the hardest-hit sections of the city, where the free black population lives and note their proximity to the Delaware River. Ask your students to review Smith’s map showing where Philadelphia’s free black population lived. What are the correlations between location and mortality?

- Additional resources for teachers on the 1793 yellow fever epidemic can be found online.

Glass lantern slide of the Lazaretto quarantine station. Frances Anne Wister Lantern Slide Collection.

Lazaretto Ghost Stories

David Barnes’s article on the Lazaretto quarantine station gives teachers an opportunity to engage students in a discussion of the ways in which “commodities, people, and news from the farthest corners” flow in and out of Philadelphia—bearing germs as well as goods—and how the city chose to guard against contagion by quarantining those suspected of carrying illness.

- Ask each student to imagine that they are an individual quarantined at the Lazaretto and have them write a journal entry from that person’s point of view. What were their symptoms? What was their experience? How long was their stay? Who helped them, and how?

- Barnes points to an incredible fact about the Lazaretto: 90 percent of its patients survived, including many suffering from serious diseases. He believes that “the mundane daily chores that had the nurses rushing about so busily” may be the reason so many Lazaretto patients lived. Have students research the routine tasks of a nurse in the 1800s would have performed and write about and/or discuss how they may have helped patients recover and prevent the spread of disease.

American soldiers returning from France. The mass mobilizations of World War I helped spread the epidemic. 1918. Philadelphia War Photograph Committee collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Homefront Casualties: Philadelphia’s Influenza Disaster

The year 1918 marked the end of World War I, “the war to end all wars.” As countries across the globe welcomed their soldiers back from the battlefield, they were greeted with an equally deadly adversary: influenza. James Higgins’s article provides a compelling look at how a parade to promote the purchase of Liberty Loans and rally support for the war effort spread the deadly epidemic through the city of Philadelphia and gives a gripping account of the macabre circumstances the city faced.

- Ask students to create a graph charting the number of reported cases of influenza, as outlined in the article. What trends do they notice from the chart? Are there months in which the disease has higher incidents? What can students infer from the data they collected?

- Engage students in a discussion focused on the global nature and trench warfare of the First World War. What role did these conditions play in causing the influenza pandemic?

- Students can experience a first-hand account of the flu’s impact on local citizens by reading the Gibbon family correspondence at the Historical Society of Pennslyvania. Some letters that provide insight into daily life during the epidemic are highlighted here.

- Ask students to read the Report on the Emergency Work of the National League for Woman’s Services in the Recent Epidemic of Influenza. Ask students to outline roles women played in addressing the pandemic. What type of work did the organization engage in?

Children recovering from polio at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia practice walking with crutches, Jan. 4, 1946. Photo by Edward Ellis. Philadelphia Record Photograph Morgue.

Polio in Pennsylvania

Daniel Wilson’s article details how funding from the March of Dimes and the vaccination technique developed by Dr. Jonas Salk at the University of Pittsburgh saved generations of children from the debilitating and sometimes deadly effects of polio. Students may use this article to learn about innovations in vaccination and the ways in which they are protected from illnesses unlike generations before.

- Ask students to read the article. Have them consider the unintended consequences of improved sanitation in causing the polio epidemic.

- Public Service Announcements (PSAs) play an integral role in public health. Getting the right message out to communities is essential in combating health issues. For this activity, have students develop advertisement campaigns targeting parents to get them to participate in Dr. Salk’s inoculation programs.

Together, the articles in this issue of Legacies provide students with an interesting look into the public health history of Pennsylvania and the United States, allowing them to explore the impact of disease on society and how illness has been managed by state and local officials. These articles allow teachers to explore the social history of epidemiology and how it intersects with studies of race, gender, and class throughout history. Teachers may also engage students in discussions of the important role of communications in distributing factually accurate information, quelling a population’s fears, and providing clear instructions for ways to stop the spread of disease and engage in healthier practices. By giving students a window into pandemics of the past, we potentially spark the curiosity of the next Salk or spur a generation to ensure the end of a disease of our time.

Dr. Karalyn McGrorty Derstine teaches US history at Gwynedd Mercy Academy in Lower Gwynedd, Pennsylvania.